Hip hop rewards hustle. Just ask Mike Schreiber. A self-trained photographer who started shooting on a Canon EOS Elan, Schreiber’s captured Yasiin Bey, Erykah Badhu, and Nas, to name just a few. It all began after college, when, working a desk job at a celebrity photo syndication agency, he figured out how to sneak into shows. “I would write to an artist’s publicist, ask for a photo pass, make up a magazine that I was working for—usually a foreign magazine because they never checked. I ended up shooting Lenny Kravitz and Oasis in ’96. I had no business being there at all! I was just having fun.” Eventually his boss at the agency found out and gave him an ultimatum—stop shooting shows or lose your job. He chose the latter. “I said okay good. And then I had six months of unemployment and I just told myself, I’m gonna figure out how to do this.”

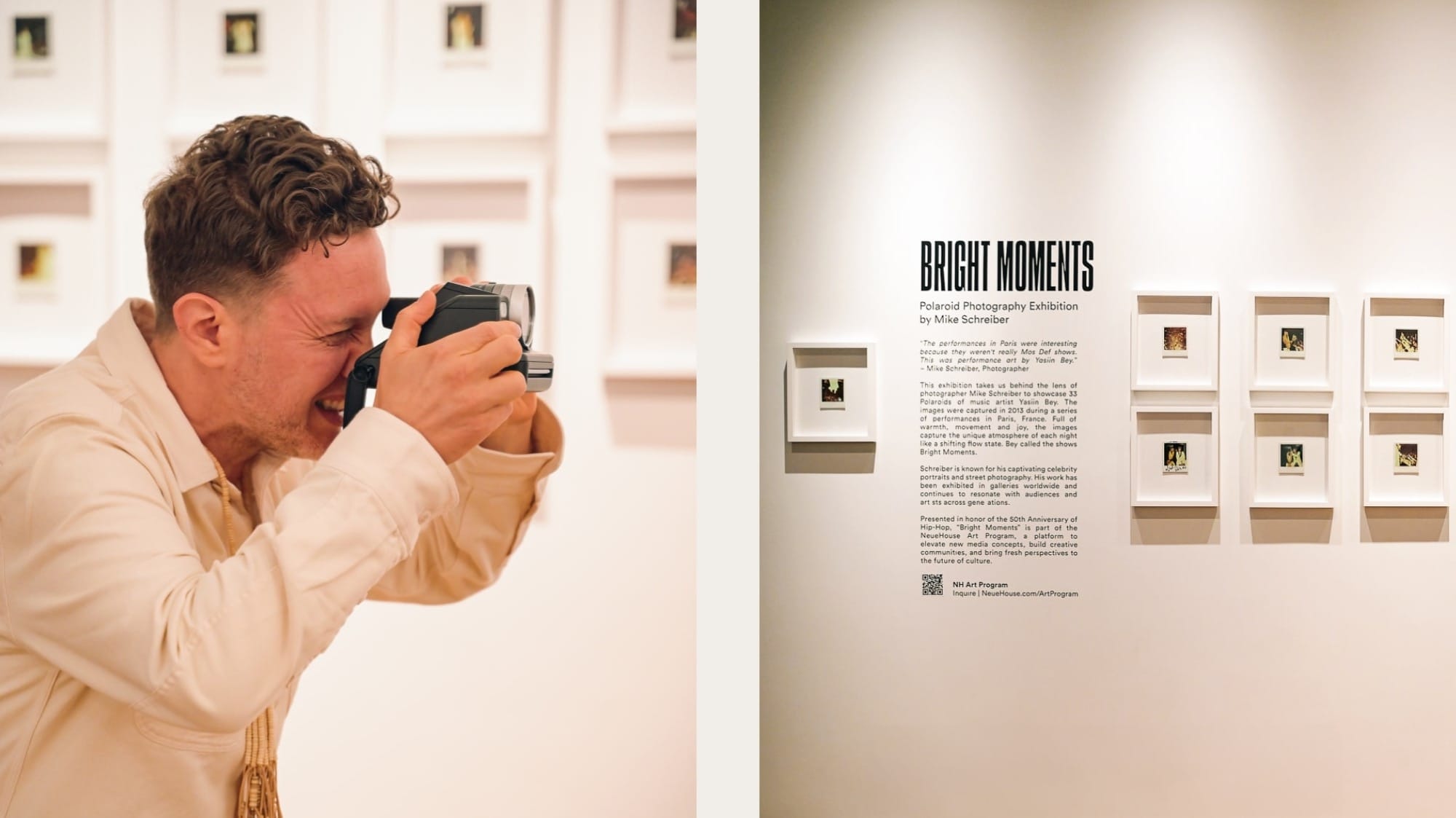

Ahead of the opening of his new Polaroid exhibition, Bright Moments, at NeueHouse Venice Beach, Mike Schreiber sat down with us for a conversation about hip hop, hustle, and capturing the moments between frames.

NeueJournal: ‘Bright Moments’ gets its name from a series of Yasiin Bey (also known as Mos Def) concerts in Paris ten years ago. How did the project come to be?

Mike Schreiber: My relationship with Yasiin goes back to the late nineties, from when I first started shooting— we weren’t friends, but the New York hip hop scene was small. Fast forward to 2013. We were both at the Paris Hip Hop Festival: I was asked to come on a radio show for my book [True Hip Hop]. I saw Mos Def written on the studio whiteboard with all the names of guests. He was coming in the next day! So I asked what time he would be there and I just showed up, hoping he would remember me. We connected like no time had passed. And he was doing this series of three shows, and he told me to come take pictures.

NeueJournal: What were the shows like?

Mike Schreiber: I’ve been to so many hip hop shows and they kind of bleed into each other. This wasn’t that. When I asked Preservation, the DJ, what he remembers [from the show], he said “all I know is he told me to bring songs that sound like the sun, the moon, and the stars.” Two hours before the show, he told the floor manager he needed 2,000 gold balloons and 5,000 red roses. Everything was atypical, even the setlist. What was interesting was that people were coming to see Mos Def, but he wasn’t doing that. He was doing his vision. That’s pretty much how he’s always been, which makes him very unique in the world, especially in the music world, especially in hip hop. And it’s fun to be on stage taking photos for that. Yasiin is like a jazz artist. You don’t know what you’re going to get, but you know it’s going to be interesting. That’s always been my relationship with him. I just show up with my camera and see what happens. And really magical things come from that.

NJ: Why did you choose to shoot with Polaroid?

MS: I can’t remember whose idea it was, but I was doing a lot of Polaroid at the time. They had gone out of business and come back, and the film was not great. But I purposely didn’t color correct them because that’s how they looked. And the show is the actual Polaroids. And it’s all there in the pictures. It is what it is. That’s one thing I love about Polaroids – there’s no hiding flaws, no editing people out, none of that. So I went and got as much film as I could get.

NJ: What drew you to photography initially?

MS: I always liked to draw and paint, mostly pictures of Jimmy Hendrix or whoever was in Rolling Stone — but I never considered the fact that when you see a band on the cover, there was a photographer there taking the pictures. In college I studied art and then switched to anthropology and took a few photo classes pass/fail. But I didn’t know photographers. I didn’t know who people like Richard Avedon were. I remember going to this Elliott Erwitt exhibition, and his pictures are really beautiful but they’re also really funny. And I thought, okay, you can be playful and have fun. And basically, if you do things well, you can do whatever you want.

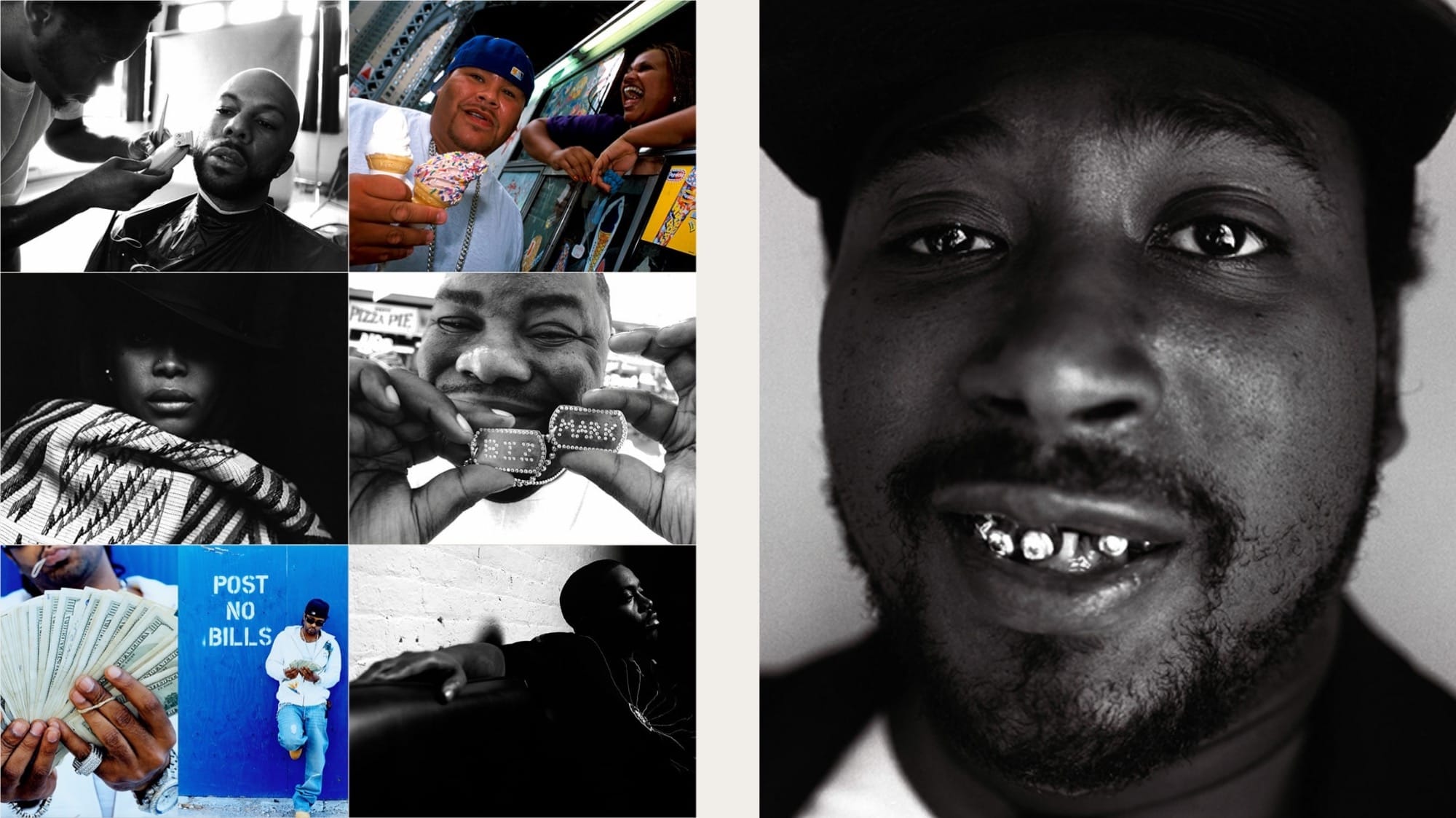

NJ: How did you break into the hip hop scene?

MS: So after I graduated from college I got a job at a photo agency that syndicated celebrity photos. I was making $19k a year before taxes. And these photographers would come in with photos from concerts and parties. I thought to myself, ‘I like going to concerts.’ And I knew if they could figure out how to do it, I could figure out how to do it. And because I worked there, I knew how to get photo passes.* I eventually got fired for sneaking into shows. I had six months of unemployment, so I just told myself: I’m going to figure out how to make money taking pictures.

During my six month hiatus a woman I used to work with contacted me and asked if I was still trying to be a photographer. I said yes, and she was the new photo editor at Spin, and she sent me on assignment to Mercury Lounge. From then on, I took the live photos for Spin. Then I’d get the Village Voice, circle shows I wanted to shoot, find out what label everyone was on, call the publicist, try to get a photo pass, take pictures, and then try to sell them. Hip hop shows were easiest to get into because they were mostly club shows. It wasn’t Jay-Z at Madison Square Garden. But wherever I was, I always tried to kill it. Every opportunity. Hip hop has always rewarded people that hustle. And I think it’s still the same. It’s a different hustle, but if you hustle you can do anything. That was my experience.

How do you think digital photography has affected the role of the photographer?

It’s different because everyone has a really, really good camera on their phone. Everyone is their own subject and can tell their own stories now. Which is much better, I think. Every single one of us is our own documenter. Some to more of an extent than others, some more truthful than others. But photography has never been particularly truthful.

NJ: What do you mean by that?

With a photograph, honesty is not necessarily the same as the whole truth. What I mean is, what you’re seeing is within the frame, you see one person’s perspective. The photographer’s, or what an editor chose to show. So it’s not a lie. But what you’re seeing [in a photo] is not the whole story. If you look at my Instagram, you’re not seeing the full picture of my life. There might have been a hundred pictures taken of mangos before I chose this one to post.

Do those limitations influence the way you think about your work?

In some ways I think not having technical training has benefitted me. I rarely did stuff in studios. I rarely use lights. For the most part, I shot the second-in-command. When you’re shooting those big names there’s a lot more you have to take into account. You can’t just run around and see what happens, which are the conditions I thrive in. More natural than “we need a concept.”

You’re known for shooting mostly in film. What are your thoughts on film versus digital photography?

I’m always conscious of the contact sheet. I don’t want throwaway pictures. I saw a Robert Frank exhibition, and they had some of his contact sheets. It was amazing because every picture he took ended up on the wall. He didn’t do five different angles of each thing. He made every decision in his mind before he clicked the shutter. That’s a real exercise. That’s the Olympics. [Creativity is] about having confidence in your decisions, and not being afraid of messing up. Not everything is going to be perfect. Obviously not every frame is going to be great. Some are going to be out of focus. That’s the thing about digital. There’s no mistakes. There’s no light leak. With Polaroid a lot of times you pull it too soon, or there’s a thumbprint on it—but that’s it, and that’s amazing.

What is your creative process like?

You know, I was shooting ODB for XXL and they wanted a concept with a location. I had just been on Saint Marks and I saw that famous photo of John Lennon at the Statue of Liberty, so I suggested that [we shoot at there], really thinking it wouldn’t happen, but it did. But even then, the best photos of the day were taken on the ferry on the way to the Statue of Liberty. It’s more natural. I like to shoot in between frames. Here’s another example. There’s a picture I took of Jim Jones counting money on the street. And it wasn’t a concept—he was doing that. My assistant was loading the camera and he just took out a wad of bills between shots. I wasn’t like, let’s take out bills and you count them and make believe you have all this cash on you. He really had all this cash. And I was like holy shit, that’s a crazy amount of money!

NJ: You recognized a moment.

Yeah. I think it was interesting because it’s genuine. I’ve always said I want to take pictures— especially when it comes to hip hop—where the artist’s mom recognizes them. Rather than the ‘character’ they are on stage.

“I’ve always said I want to take pictures— especially when it comes to hip hop—where the artist's mom recognizes them. Rather than the ‘character’ they are on stage.”

What is a piece of creative advice you might share?

One of my favorite stories from when I was starting out is, in 1999, a photo editor I had worked with before called and asked me if I could shoot DMX for a feature. It was the first time anyone had really asked me to shoot portraits. DMX had just blown up. This is one of the biggest stars in the world—and I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t know what a light meter was, I didn’t know people had assistants, nothing. I went to the Def Jam in Tribeca and the publicist said “DMX is outside in the alley with some people. You have fifteen minutes.”

I thought, alright, this is my chance. So I go out there by myself, 5’7, I have my camera bag, kind of not getting anyone’s attention. And in my head I’m just like, fifteen minutes, fifteen minutes. And then I made an announcement that I needed everybody except for DMX to move to the other side. And it was like a scene in a movie where everything stops. Everybody turned and was like, “who the fuck is this guy?” Thankfully, X was like, “oh he’s cool. ” And I was able to take pictures of him, and they came out great. But that’s the thing. I had fifteen minutes. I knew I couldn’t go back to the magazines and say I couldn’t get anything because he was talking to his friends. I couldn’t have excuses that they weren’t nice to me or that I had to wait for them to show up. And I didn’t want to go home and watch TV. You just have to know what you want. And then go for it. You have to think, “okay I’m gonna be here for 15 minutes.”